This article was written on the occasion of last year’s Women’s Day for a print magazine called Eclectic Vibes. Considering the fact that the day has arrived again, I am reproducing it in this site.

___________________________________________

Asghar Farhadi’s A Seperation has more or less taken the world by storm. Nevertheless, discussing its success in the festival circuit is merely stating the obvious. What I find more interesting is the pivotal female characters in this and for that matter several other films from Iran in particular and the Middle East in general as this is a region that does not offer a very optimistic scenario with regards to women empowerment.

It is all the more important because the strong female character are rarely seen in the mainstream Indian cinema nowadays. So, keeping the Women’s Day in mind, I am discussing three women centric films that represent the restrained yet potent film industries of the Middle East. The first one is of course A Seperation from Iran which is the flavour of the season. Another lesser known film that I want to discuss is the Egyptian film 678 by Mohamed Diab and I will wind up with Siddique Barmaq’s festival favourite Osama. These are not necessarily the best films of that genre and from that region but they offer us a contrasting insight into three different societies, one hanging onto the status quo, one yearning for change and one descending further into chaos.

A Seperation (Iran, 2011)

A pregnant woman (Razieh) gets a housekeeping job in a well to do Iranian couple (Simin and Nader). She has a little daughter and her ill tempered husband cannot stick to any job. On the other hand the family she works for is about to fall apart as the husband and wife are on collision course, much to the dismay of their teenage daughter and her grandfather who is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Simin wants to move to the US for a better future of her daughter but Nader resists and hence she files for divorce. As the story progresses, the internal conflicts start taking toll on their personal lives. One day Nader discovers his elderly father lying unconscious on the floor and also suspects that some amount of money was stolen. So, he confronts Razieh and after an argument throws out of the house and injuring her. Later on it was revealed that she has suffered a miscarriage and hence Nader must face legal punishment or settle it off court by paying a good amount of money to the poor family.

The beauty of the film lies in its moral ambiguity and subtle emotions. There is a conflict between the abhorrence towards the man who pushed a pregnant woman and the empathy towards the same man whose family is falling apart. One may feel for the poor lady who loses her child but cannot ignore the understandable greed for the settlement money. The most innocent and honest characters turn out to be the children from both the families. But then, that is expected from the Iranians who are always good at making children act.

A Seperation, through a humane tale, also mirrors the contemporary Iranian society in a realistic manner. It is not as Talibanized as one would like to think. Women do work and have a say in the important matters but there is always a fear of authority that is looming large. That is why when Razieh must change the cloths of the ailing old man, she calls a helpline and asks if that will be considered blasphemy. Nevertheless, eventually the film connects because of it tells a universal story of a dysfunction family that everyone can relate to. It keeps the emotions restrained rather than dramatizing it too much, which would have been the easier way out. Farhadi is supported in this venture by an excellent ensemble cast of natural performers.

678 (Egypt, 2010)

Somewhat based on true events, 678 tells the story of three women in a society that is in the threshold of great change. Fayza is a lower middle class governmental employee married with two children. Every day she commutes to work on a crowded bus numbered 678 and almost every day she is subjected to sexual harassment at the hands of deprived male passengers. The second woman Seba hails from a wealthy family but is also a victim of a gang assault and hence a vocal supporter of female rights. The third woman is Nelly a much younger woman with strong opinions who also suffers a sexual assault and gathers the courage to file a historic lawsuit in a nation where the subject itself is considered taboo. Fayza gets influenced by the feminist sermons of Seba and she eventually resorts to violence by attacking assaulters. She uses a small knife to attack the lewd males where it hurts the most, their genitalia. But it isn’t easy being a feminist in a conservative land. Enquiries ensue and the women must give up or gather the courage to stand up openly and fight.

This is the most hopeful of the three films discussed here and is not surprising considering the wind of change that is sweeping the country. Director Diab is also apt at handling lighter moments such as the hilarious interrogation of the stabbed molesters. Through the film, he also successfully portrays the class difference in the society. Fayza is the bravest of them all, but she is also the first one to be weakened by adverse conditions and doubt her own acts owing to the repressive background she comes from. But eventually her more liberated friends make her have faith in herself and eventually it paints an optimistic picture of a brighter tomorrow in a society that is finally bracing for a change.

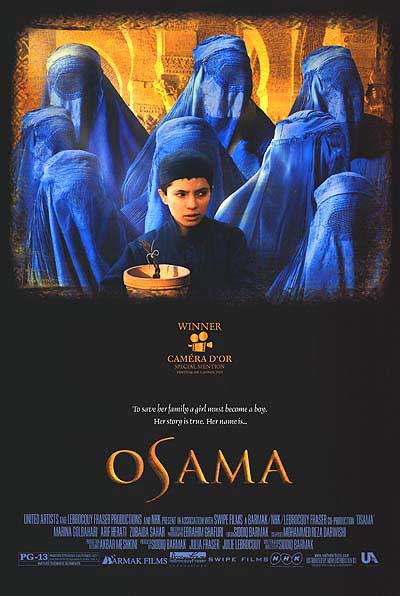

Osama (Afghanistan, 2003)

In case anybody is wondering, it has nothing to do with the dreaded terrorist (I did when I first heard the name). It is about a little girl who comes to be known as Osama. The Talibans have taken over the country and banned women from all possible spheres of social life including the workplaces. Osama’s family consists of her mother and grandmother and none of them can now work for a living. The male members of the family are already dead but the stubborn, fundamentalist regime doesn’t consider it a reason enough to compromise with their “ideals”. So, the family finally comes up with the only possible solution, making young Osama masquerade as a boy and do small menial jobs to sustain the family. But even that is easier said than done and death by stoning is the standard penalty for such “crimes”.

This must be the most pessimistic film out of these three and probably out of all films I have even seen in my life. It offers no hopes and has no redeeming features. It starts with a somber mood and the prospects get even darker for the ironically named protagonist. It is believed that the director originally had a brighter ending in mind but eventually the ground realities made him opt for this bleak finale that is enough to shake anyone’s conscience. This film was another festival circuit favourite when it was released and made Barmak the face of Afghan cinema. It is a must watch for anybody who wants to have a peek into the Taliban regime but if anybody is looking for a lighter and satirical portrayal of contemporary Afghanistan, Barmak’s Opium War (2008) may be a more interesting option.